Menu

- About

- Categories

Categories

Maybe someday

34

/100

I Index Overall Rating

Readers

Critics

Scholars

N/A

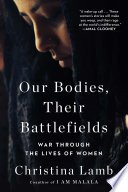

Author:

Harold McGee

Publisher:

Penguin Press

Date:

October 20, 2020

Smell is such a powerful and revealing sense because it detects actual little pieces of things in the world. Text and 200 tables cover this topic, in a book by an expert on the chemistry and history of food science and cooking.

What The Reviewers Say

Sam Kean,

The Wall Street Journal

The Wall Street Journal

You’ll never look at a charcuterie plate the same way after his breakdown of how the discarded skin proteins, foot bacteria and sweat inside your socks essentially recapitulate the transformation of milk and brine into prized aromatic cheeses. Still, fans of Mr. McGee’s culinary writing won’t be disappointed—there are several hundred pages devoted to scrumptious foods, both raw and cooked.

Rachel Syme,

The New Yorker

The New Yorker

This collision of the mundane and the revelatory makes McGee’s book as enjoyable to thumb through as the Fragrantica forums, though his guide is much better researched and far less baroque. It unfolds like a set of smart answers to essentially silly questions about quotidian life. Ever wonder why sweaty armpits stink? And, in the worst cases, why they stink of shallots in particular? McGee reports that the apocrine sweat glands, which kick into high gear during adolescence, do their best to hide the evidence of their own microbiomal bouquet. Sugars and amino acids bind to volatile, potentially rank molecules, thereby preventing the release of any foul smell. But when bacterial interlopers, such as bacillus and staphylococcus, break these bonds and 'liberate' compounds like hydroxymethyl-hexanoic acid, then the full power of B.O. is unleashed: 'rancid, animal, cumin-like.'.

Caren Nichter,

Library Journal

Library Journal

... exhaustive.

Tony Miksanek,

Booklist

Booklist

McGee elegantly explains olfaction.